A Bold Traveller

Interview with Gretta Louw

Han Yan

Location: Broun’s Tea Bar, Munich

Time: July 12, 2016

Interviewer (Q): Han Yan

Artist (A): Gretta Louw

I first met Gretta in December 2015, at the exhibition hall PLATFORM in Munich. She had co-organized a discussion on cyber performance with Helen Varley Jamieson and the net performance pioneer, Annie Abrahams, presented her work. At that time we did not speak together a great deal. Later I did research into Gretta’s work. She has focused for a long time on the cyber world and has tried to explore the psychological mechanisms behind it. After I got to know her better, I like to call her “a bold traveller”. This reveals a lot, not only because of her personal experience, but also about the subject matter of her art.

Part One: From Psychologist to Artist

Q: Why did you study Psychology at the University of Western Australia?

A: I have always been interested in people. Is there an internal process of being human? How does it work? Such questions attract me.

Q: Did you enjoy your studies?

A: Absolutely! I learned a lot during my studies, such as how to think critically; how to design an experiment; research methodologies, etc.

Q: After your studies did you work in this field?

A: Yes. I worked for one year as a crisis advisor for a suicide prevention service.

Q: Why did you decide to be an artist?

A: During my former job I started to question how mental illness is diagnosed and how psychology - as it is currently practiced - impacts our society. I travelled a lot and lived in various countries. I wanted to find another way: dealing with the same problems but in a distinctive way.

Q: Was this change difficult for you?

A: I come from an athletic family. I was a competitive swimmer when I was young, so it was hard to image that art would become my profession. On the other hand, I had already been involved in some artistic endeavors in my early life. I took a lot drawing and oil painting classes at various places. Art has always been with me.

This “travel” between two different spheres is one of Gretta’s most attractive experiences. During our two-hour-interview she was always concentrated on our topics and did not need much time to respond to my questions. She has a firm voice and a clear head. Maybe her career in psychology has a strong effect on her modus operandi, or vice versa.

Part Two: From Australia to Germany

Q: Your homeland is located in another hemisphere. How is the contemporary art scene in Australia? Dose Eurocentrism play an important role?

A: The mainstream does suffer from Eurocentrism, but at the same time there are several different perspectives, for instance, biennales and triennials focusing on Asian, Australian, Indigenous and Pacific art.

Q: Why did you decide to move from Australia to Germany? What does it mean to you?

A: When I started to draw, I never called myself a painter or an artist. When I arrived in Berlin in 2007 I realized what I have already done in Australia - my background in psychology - was related to art; that this was the perfect basis upon which to expand my practice. Being an artist means not only to represent the world visually, but also to question it as a researcher and an activist. It has taken me a very long time to define myself.

Q: Could you tell me a bit about your artistic endeavors in Berlin.

A: When I arrived there in 2007, electronic music and contemporary art dominated the city. I was still painting then, but I realized that I wasn’t inspired by the painting that I was seeing around me. I got a cheap studio in the former no-man’s land where the Berlin Wall had stood and for a year I only produced works in black and white, using every and all materials I could within this one limitation. I was not satisfied with creating decorative work. This led me to black-and-white photographs, which were produced in series and then it was a natural progression into GIF-animations. In a way, that year alone in the studio (and in Berlin’s museums and galleries) was my education in art.

Q: What is the most impressive thing about Berlin’s art scene?

A: I left Berlin in 2011. At that time small project rooms were very popular in the city. A lot of intellectual programs took place there. I really like them. Art Laboratory Berlin - working with them changed everything for me.

Q: You also lived in Mannheim for three years. How is the artistic atmosphere there?

A: Although this is a city dominated by industry, I know people there who understand contemporary art very well, such as Benedikt Stegmayer, curator and art historian, who directed the city gallery of Mannheim at that time. We did some projects together and I was awarded the Art Prize of Mannheim in 2014. I am thankful for all the support from the city. These three years were very important for my career.

Q: In a documentary film Sally Mann advises young people: do not travel a lot, stay home and focus on your surroundings, you will become a great artist. Do you agree with this?

A: I think Sally Mann’s words mean that an artist today does not have to move to New York or Berlin. You can live in a small city and keep on working and building your networks via social media. It gives artists more freedom.

Q: Now you have settled in Munich. What do you think about the city in regards to art?

A: Munich is great for me. I know some media artists in the city and we can exchange our ideas. This means a lot to me. There are several fabulous museums in town such as Haus der Kunst, Museum Bradthorst, Sammlung Goetz and others. However, Munich still lacks project rooms that function like small professionally-run institutions such as the places in Berlin.

Gretta’s words lead me to think about the kind of culture institutions we need in the future. Do we still need large museums keeping orthodox history of mankind? Orhan Pamuk’s manifesto delivered at the International Council of Museums (ICOM) conference in 2016, sets forth the idea that in the future we need small museums that care about more individual stories and not about a national history.[1] Gretta’s thoughts on cultural institutions coincide closely with Pamuk’s view.

As a traveller Gretta has left tracks all over the world. I am particularly moved by her footprints across Germany from east to west. It might give an overview of contemporary art in this country. More importantly, it could help us to understand that national art history is comprised of artists’ personal experiences.

Part Three: From Virtual to Reality

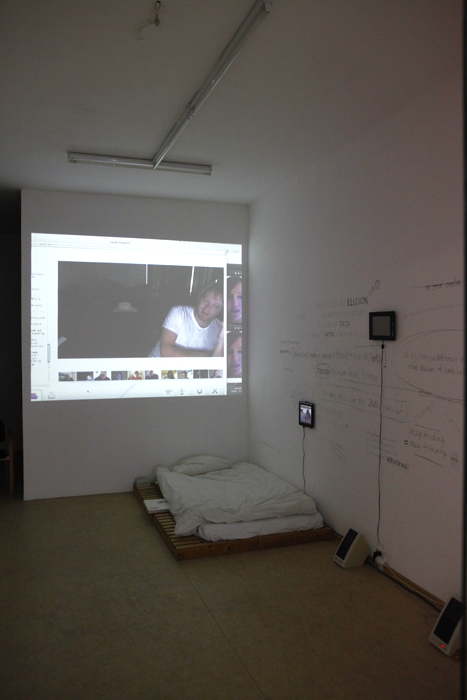

Q: In 2011 you did a performance Controlling_connectivity (img.1) in Art Laboratory Berlin. Could you talk a bit about how this project started?

A: I wondered how our communication and relationships had changed since Facebook was launched in 2004, and since it became more commonly used a few years later 2007. Some thought this social medium would renew the world and build more democratic processes, governments, movements. Actually the platform is based on an alignment with profit-driven data-mining and hugely beneficial to national surveillance agencies. My first question was how this new technology impacts us. Some studies show that if we spend eight hours every day surfing the Internet, our brain will undergo neurological changes. But whatever you do eight hours a day, such as playing chees or driving car, will change your brain – this is the basic premise of neural elasticity. So I wanted to perform a sort of auto-experiment. Controlling_Connectivity was a 10-day online performance. I lived in a small white-cube gallery without daylight or visitors. I talked to people only via social media, and I was available for contact 24 hours per day. This was the basis of the project.

Q: Did the performance meet your expectations at the end?

A: Actually I didn’t have clear expectations; I really went into an open mind. But the whole process was interesting. The people with whom I spoke were very diverse. They asked me many questions, most of them very intelligent, challenging, but of course there were a few uncomfortable moments. I wanted to know where it will all end, if there is unlimited expansion of communication. What does this dystopia look and feel like? What if there is no ending at all?

Q: Before the implementation did you define your target group?

A: Not at all. Actually, I expected more sexual harassment.

Q: Really?

A: Yes. But honestly, it was not as much as I thought.

Q: Would you see it as a good sign?

A: In this case I had a positive experience. It actually gave me a better opinion of human nature (laughs).

Q: That is very interesting. Most of your works could be thought of as critical of the Internet and social media. But this project demonstrates an optimistic view of human nature. A famous antique Chinese cannon, The Three-Character Classic, states: “ Men at their birth, are naturally good.”

A: Exactly! The Internet is such an important research source nowadays. Issues like sexism, racism, intersectionality are not reported or discussed enough in the mainstream media. But you can do intensive research online: via social media (Twitter mostly) you can find people to discuss those issues and can also read in-depth commentary. That is much rawer and mostly more forward-thinking than media outlets can provide.

Q: It leads to another issue—censorship. For instance, the situation has altered radically since the social media, WeChat, established in China in 2011. Information posted on it spreads rapidly. It is more difficult to cover up the truth in comparison to the past under strict censorship.

A: In this case it helps people to challenge authority. Social media definitely has a positive aspect. One can shape one’s own thought and collaborate with others.

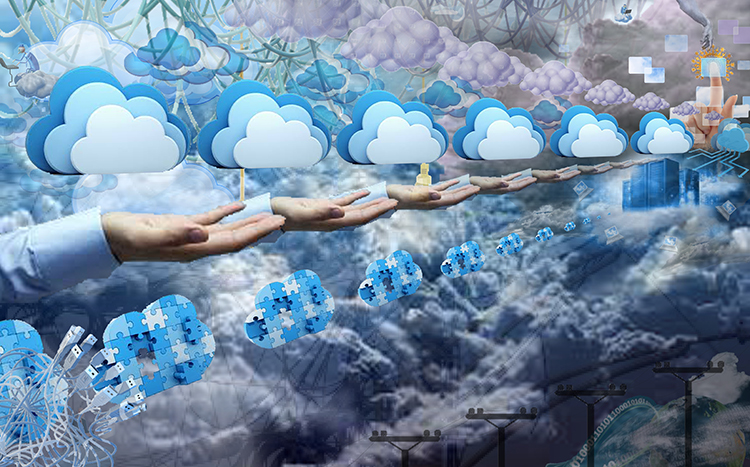

Q: Now I would like to talk about The Cloud (img.3). In the context of classic art history, the cloud symbolizes Heaven. Is it here a metaphor of a data utopia that dosen’t exist.

A: Exactly. I wanted to deconstruct the glossy images strategically presented to sell supposedly glamorous products.

Q: Do you mean the marketing strategies around so-called cloud computing?

A: Right. A good example could be our smartphone. What is inside the device and how does it work? Where is my data? How is it stored and transferred? Such common questions are - for the average user - totally unknown. One would not deposit values in a bank without knowing in which safe it is kept. The marketing strategies such as design, presentation and sales hide all these thoughts behind a sanitized, slick front. The presentation of ”the cloud“ or cyberspace as a disembodied and intangible world – like a cloud – goes a long way in preventing people from questioning what is really happing with their data, or who is making their iPhone.

Q: Don’t you think the Internet is a virtual world?

A: I totally disagree. A lot of artists explore the materiality of the Internet, such as Ben Mendelsohn’s Bundled, Buried and Behind Closed Doors, Timo Arnall’s Internet Machine, among others. Their works reveal that the Internet is palpable and visible. This is one aspect. There is also another new realistic view, that is to say, everything that can be experienced, is real. For instance, there are some studies of Facebook’s comments, which say they could cause a neurological and chemical change in the recipient’s brain. Our life is actually affected by it. And from this viewpoint, also, the Internet is real, and so are all our interactions through it.

Q: Was it your original intention to install a server with many cables flying out for The Materiality of the Internet (img.2)? Is it an aesthetic or more substantive decision?

A: Both. In making art, there are naturally aesthetic elements, choices. I wanted to show in the installation what this media made of: it is not disembodied or abstract, but consists of masses of materials and resources. I believe if people see the tangible, physical corporeality of the Internet, they will seriously rethink the impact of technological “improvements”.

Q: The Cloud (img.3) is a collage, which is made up almost entirely of advertising images of cloud computing. Where did the idea come from?

A: The way this strategy represents itself is so absurd and ridiculous. I try to put a hook in my work, in order to ensure that certain aspects are no longer overlooked and the viewer can stop and think about how this technology affects us. Today everything runs so intuitively, almost automatically; our devices, the GUI. The marketing imagery associated with cloud computing – cartoon clouds, glowing servers in the heavens, white hands skimming over illuminated displays – is so oppositional to the reality of the actual the product. That is why I took images I found from the Internet, and duplicated, exaggerated, highlighted them to make this absurdity, which we’ve become to accustomed to, visible.

Q: What is the fundamental spirit of the Internet?

A: Wow, massive question. I think, these days, all the big players are trying to establish their own island on the Internet; their own nation. We are living through a hidden battle between huge digital empires, and we must discuss the colonialist aspect of this proprietary systems – Apple is perhaps the worst culprit here – or massive impact on and tracking of your online activity, like Facebook, or Google’s attempts to own not only the web, but also cars, books, space travel; basically to grow their sphere of influence so large that they swallow the world; all of these are examples of a colonialist power – a new “nation“-building, the expansion race of new, post-nation superpowers.

Q: A new colonialism of our age.

A: Yes, totally – although the colonialism of past centuries is also still with us.

Q: It is only about earning money. The companies don’t care about what really happens on the platform.

A: Exactly. This is a good example of how we as artists and activists could use the opportunity to change things.

Q: Could you be more specific?

A: Marc Garrett talks about a nice concept—culture hacking. This is a great term for the ways that ordinary people can use existing technology and platforms for different purposes that we have not seen before. Not everyone has the skills or resources to build a new tech structure, but we can make good use of existing mechanisms and technologies; find ways to subvert the prescribed use or guidelines and bend it to our own purposes. A great example of this is Twitter. Like any other social media platform, Twitter is designed to illicit user generated content for the purpose of making a profit. It has not (yet) been very effective at the latter part, but the platform has been central in the development of many of the most interesting recent political and philosophical movements, from Arab Spring to #OWS and #BlackLivesmatter or #SOSBlakAustralia.

Our conversation was interrupted after two hours. Gretta had to pick up her son from the nursery. And again—travelling from artist to mother. I am sure that we could start a new chapter only to talk about this issue.

We live in an age in which capital manipulates the art market. Maybe being an artist is much harder than at any other time in history. But Gretta is decisive. She travels between different dimensions without hesitation or doubt. She has a remarkably keen insight into our society and human nature, just like her work.

[1] Sheng, Wenjia (translator, editor), From Epic to Novel, Orhan Pamuk’s Manifesto of Future Museums, Tanchinese, July 09, 2016. Quote translated by the author.